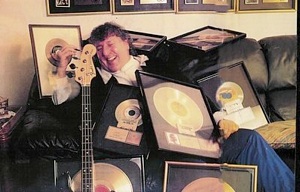

“WHO IS BOB BABBITT

AND HOW DID HE GET

ALL THOSE GOLD RECORDS?”

By Allan (Dr.Licks) Slutsky

The second part of this question is easy to answer. Bob earned

his 25 Gold and Platinum records by playing his ass off on over

200 top 40 hits. The first part of the question, well that requires a

bit more explanation.

Detroit, 1967: Bob has received a call from the local record company that exports the city’s second most famous product. Their celebrated house bassist is having personal problems, and they want Bob to pinch-hit for him on a session. In an atmosphere that could be described as cliquish and skeptical, at best, the producer, the arranger, and the rest of the musicians descend upon Babbitt with a litany of instructions on how to sound and play like their missing comrade. Nobody in the room says it, but they all expect him to fall short.

A decade later, Bob finds himself in New York City, where he has been called into the studio to cut an album of traditional Italian songs. The producer is a famous Mafia don (who will remain anonymous for the health of everyone involved). On this date, in addition to being told how and what to play, he's been given more instructions. Wear a suit, don't make any mistakes, smile, and most of all, don't even think about walking into the control booth where the don is holding court.

Now Bob's playing bass for a Gladys Knight & the Pips project for Buddah Records. The rhythm section is huge. There are just too many instruments and too many written notes on his chart, and about 20 take backs, rigor mortis began to set in on the groove. What a nightmare! Of course, the producer's solution is to say (oh no, here it comes):

"Can you try to play something like Chuck Rainey would play?"

This is your life, Bob Babbitt. Will anyone ever just let you be yourself? Okay, hang in there- there is a silver lining in all of this. Gladys' producer eventually came to his senses, sent half of the rhythm section home, tore up the charts, and told Bob to play whatever he felt against the chord changes. The result was a double-platinum, Grammy-winning #1 pop hit called "Midnight Train to Georgia."

FROM STEELTOWN TO MOTOWN

Don't get the impression Bob Babbitt is anxiety- ridden about all of this. If body language counts for anything, his rugged features and six-foot- two, offensive-lineman's frame convey about as much tension as that of a Monday Night Football fan in a recliner with an empty six-pack next to him. Let’s just say he's "concerned." His career-long struggle for self-expression is much like one of his relaxed grooves: It's something that's always been there but never gets in the way.

Bob's long journey didn't start in New York, Detroit, Los Angeles, or any other city with a rich studio tradition. It began in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a town renowned more for its steel-making than its hit-making. Born Robert Kreiner to Hungarian parents, Bob received classical training on upright bass, although, he says, the gypsy music to which his family exposed him at a young age was far more influential. At 15, inspired by early rhythm & blues hits like Bill Doggett's "Honky Tonk" and Red Prysock's "Hand Clappin'," he began performing in local nightclubs. Two years later, after hearing his first electric bass in a local club, Bob traded his upright for a '60 Jazz Bass, using the 1-2-4 classical fingering systern on his new instrument until he could figure out how to work in his 3rd finger.

In 1961, because of limited job opportunities and low wages in Pittsburgh, Babbitt turned down a music scholarship and moved to Detroit, where he worked on construction crews during the day and played clubs at night. Within a year he had joined a local band, The Royaltones, that provided his initiation into Detroit's blossoming studio scene. He charted seven or eight records with The Royaltones, including a Top Ten hit called "Flamingo Express." The group caught the attention of singer- guitarist Del Shannon, and they became his touring and recording band through 1965.

As Bob's reputation grew, so did his recording schedule. One frequent employer was local R&B producer Ed Wingate, who owned Golden World studio. During this period Babbitt first came into contact with some of Motown's moonlighting musicians, including keyboardists Joe Hunter and Johnny Griffith, guitarist Eddie Willis, drummer Benny Benjamin, and, most important, bassist James Jamerson, the troubled genius whose career would crisscross with Bob's for the next seven years. "On my first Wingate session" Babbitt recalls, "I saw a list of musicians posted on a wall. It had the names of Jamerson and eight other bassists. I said to myself, Man, I'm never gonna work here-but I wound up doing so much work there they had a cot brought in for me.

By 1967 Bob was on a roll, as the word spread amongst Detroit's producers that there was another bassist in town besides Jamerson who could make some magic in the bottom end. The three or four dates a month Babbitt had been happy to get a few years earlier quickly turned into seven or eight long sessions a week. In addition to steady work at Golden World, he was busy at United Sound, Terashirma, and just about every other studio of any consequence in the Detroit area--except for Motown, which was still Jamerson's realm. Babbitt played on some classic R&B tunes during this period, including "I Just Wanna Testify" by the Parliaments, "Love Makes the World Go Round" by Dion Jackson, and "Cool Jerk" by the Capitols.

"I'll always remember the 'Cool Jerk' session," Babbitt states proudly. "It was the first date I played on when I instantly knew it was a hit. It also stuck out in my mind because the Capitols were actually there, which was rare for a Detroit session. In New York, the artists were always at the date, doing reference vocals with the rhythm section so you knew what the song sounded like. In Detroit, you never knew what the song was about until you heard it on the radio. The Detroit producers usually just cut a rhythm track and then wrote a song to it.

"George Clinton worked like that, too. He was one of my favorite guys to record with, although I have to admit, I wasn't quite ready for his transformation (as leader of Parliament/Funkadelic); George was one of the cleanest cats around-he always had on a suit and a pressed white shirt. About two years after I had cut 'Testify' with him, I got called for another Parliament's session at Terashirma. I was looking down into the studio from the second-floor control booth, and I saw this guy who looked like he had taken a piece of canvas or burlap, thrown paint on it, and cut a whole in the middle for his head to go through. His hair was pointing straight up. I had no idea who it was until somebody said, 'That's George Clinton.' I said, 'You gotta be kidding me!'

"Edwin Starr's" Agent Double 0 Soul was another great date, because it was my first contact with Jamerson. We were doing a two-bass session at Golden World, and I was kind of nervous because all of the top Motown guys were there-Jamerson, (drummer) Uriel Jones, and I think either (Keyboardist) Earl Van Dyke or Johnny Griffith. I had cut the original part, but they decided to redo the tune. James and I divided up the bass part; one of us played an eighth-note pedal and the other played a figure on top. As it turned out, they used the original track anyway."

Reflecting on his playing ability at the time, Bob says: "I was a good sight-reader, but Golden World was pretty loose. The guys at Motown had it a lot tougher, because it was more structured over there. I used to get accused of overplaying from time to time, but those problems faded as I matured. Listening to some of the great bassists who came into town to perform at the Minor Key (a jazz nightclub) helped me a lot. My influences at the time were Ray Brown, Charles Mingus, Paul Chambers, Monk Montgomery, and Jamerson. Ray Brown's Bass Method (Mail Box Music) had a huge effect on me. Even though I'm not really a jazz player, I picked up a lot of things from those guys. I once saw Mingus pop his G string on a gig, so I tried it on a Golden World session. The producer said, 'Don't ever do that again.' Of course, now everyone does it.

"The equipment I was using also had a lot to do with developing my style. I had been playing the '60 Jazz Bass on all of the RoyaItones and Del Shannon stuff, until a producer asked me to use a Precision, so l switched to a red '63 or '64 P-Bass. That was stolen a few years later, and I bought one of the first CBS Precisions, which I still play. At the time, I strung it with LaBella flatwounds and used either the mute or a sponge to deaden the strings. When the strings got gunked up, I'd boil them in lemon water to bring them back to life. Most of the dates were 4-track, and I was usually recorded direct. A few of the studios made you bring an amp, which in my case was either an Ampeg B-15 or a Kustom. We never used cans (headphones); we listened to a big monitor in the middle of the floor, just like at Motown."

HITSVILLE USA

"Just like at Motown." Those were the magic words. Being part of HitsviIIe's staff was the dream of every musician in Detroit and Babbitt was no exception. He had tried to break into the company in 1965, by auditioning for the Supremes road band, but was talked out of it by Ed Wingate. Two years later, a second opportunity presented itself when Motown founder Berry Gordy tried to eliminate all competition in Detroit by buying out Golden World.

Bob had been playing some live dates with Stevie Wonder, so Gordy's move left him perched right on Hitsville's doorstep. "My first Motown date was a Stevie Wonder song called 'We Can Work It Out.' My immediate impression of [Motown's] Studio A, was how good they made the bass sound. It made you feel as if you could do no wrong. In terms of practical matters, like working with producers and engineers, those were the best music lessons I ever had. For one thing, I learned that most of the time when people say, 'You sound great,' they're not talking about your technique or the notes you're playing. They really mean the sound itself. I also learned that if the music doesn't feel right, the first thing they're gonna do is blame the bassist or the drummer, so feel is more important than the notes."

Because of the overwhelming presence of James Jamerson within the company, Babbitt soon found that working in Studio A was a bit more complicated than just showing up, plugging in, and cutting a hit. "Working at Motown was the hardest thing I ever did, because I always felt like I was in the hot seat," he sighs. "I cut 'Touch Me in the Morning,' 'Signed, Sealed, Delivered,' 'Smiling Faces,' 'War,' 'Tears of a Clown,’ and a lot of other hits for the company (see discography), but I never felt really secure. I always felt I had so much to live up to, because of Jamerson. On a lot of those sessions, I knew that the producer and the rest of the musicians (who called themselves the Funk Brothers) wanted James, but he was going through a lot because of his drinking problems. To make matters worse, sometimes he'd come into a session where I was subbing for him and watch.

"One time they called and told me to get right over to the studio. Everyone was in the middle of a session, but James was messing up so we both played. One of the guys was bustin' on him, saying, 'You gonna let this white guy run all over you? But it wasn't malicious. Eventually, I became good friends with all those guys and was accepted into that circle. They just wanted to kick James in the ass and snap him out of it. Everybody wanted to see him do well.

"He was a great guy, but if you hung around him, you had to run into a problem sooner or later. One time, the Platters hired Jamerson and some of the other Funk Brothers to play some live gigs around the Detroit-Dearborn area. James was packing a gun, because Dearborn was pretty hairy back then. At the same time, Luther Dixon, who produced the Platters, hired me to cut 'With This Ring' and 'I Love You 1000 Times.' When I walked into the studio, there was James sitting at the organ. He said, 'I'm playing the session tonight,' and when he leaned back I could see the gun in his waistband. So I laughed and said, 'Well, I guess you are,' and turned around to leave. Luther stopped me and told me not to worry about it. Eventually, James just left.

"But we genuinely liked each other. James didn't hold grudges. A few days after that incident, I was in Golden World and James came in with his bass, kicked everybody out of the room, and said, 'Come on, Bob, let's go!' We played for hours. Boy, I wish there had been a tape recorder running, because there was some serious stuff bouncing off those walls."

Between 1970 and 1972 Babbitt, like Motown, was going through a transition period. Work had slowed down, and he was involved with a lot of unfocused and unfinished projects. Jeff Beck and drummer Cozy Powell came into Hitsville to record with Bob and some of the other musicians, but nothing ever came of those sessions. And Beck's offer to take Bob back to London with him as part of his band was blocked by Motown, because he was under contract. A company-sanctioned Babbitt solo record never got off the ground; neither did an album project with a group called Scorpion, of which Bob was a member. To supplement his income, Babbitt became a professional wrestler for six months, but he wisely chose to retire before Killer Kowalski had a chance to bite off his ear.

In 1972, just as everything seemed to be falling apart with the imminent departure of Motown to the West Coast, Bob got the opportunity to make a once-in-a-lifetime artistic statement on Marvin Gaye's What's Goin' On. "Marvin and [arranger] Dave Van dePitte basically left us wide open to create," recalls Bob. "'Mercy Mercy Me' was just a chord chart, 'Inner City Blues' had a written figure, but I was told to improvise off it. We all knew we were going into uncharted territory, but the album became Motown's all-time biggest seller."

SOUL SEARCHING

In another life, Babbitt must have been a stockbroker. Like a Wall Street veteran who knows just how long to ride a stock and just when to sell, Bob has kept his lengthy studio career alive by knowing when it's time to move on. In 1972, when Arif Mardin and other New York arrangers and producers began trying to convince him to relocate to the East Coast, that was his cue.

Bob moved to New York in 1973, and his first dates included Mardin projects for Bette Midler and Barry Manilow. Within a short time, Babbitt and drummer Andrew Smith, another Motown refugee, became one of the hottest new rhythm sections in town; producers recruited them to record with everyone from Stephanie Mills, Jim Croce, and Bonnie Raitt to Engelbert Humperdink and Frank Sinatra. Philadelphia International Records also took notice of their work, and it wasn't long before Bob was commuting back and forth to Philly to work with legendary producer Thorn Bell on such Spinners classics as “Then Came You," "Games People Play," and "Rubber Band Man."

In the rare moments when Babbitt had time to sit back and ponder his good fortune, he began to realize there were drastic differences between the three cities in which he had worked. "In Detroit and Philly, there was always magic when you cut," he observes. "In New York, many guys looked at it more as a business than the family thing that happened in the other two cities. But playing in New York forced me to learn a lot of different styles, because there was so much going on there. I started checking out rock bands like Aerosmith, Edgar Winter, and The Who--particularly what John Entwistle did on 'My Generation' and 'Magic Bus,' which knocked me out. It was all new to me, because my background was in R&B. I also had to change the way I played, because the New York approach to the instrument was different. In Detroit and Philly, it was a soft touch; New York, they wanted it harder and more aggressive, so I bought a '58 Precision and switched to Rotosound strings to accommodate the engineers and producers. I also started experimenting with sounds. I had tons of effects pedals; they would cut one track with effects and one without, and then they would choose between the two."

On a personal level, New York had a profound effect on Babbitt. He went through a period of soul searching, questioning his long-time role as a sideman. "Throughout my career, I've been asked to be Jamerson or Chuck Rainey or Joe Osborn," he points out. "This was the way producers communicated with me. I had never really thought about it. It used to bother me, but I came to realize the only way I could deal with it was to try to accommodate everyone while waiting for those occasional dates when a producer would just let me play. In Detroit, the guy who would do that was Norman Whitfield; on the East Coast, it was Arif Mardin and Thorn BelL Thorn had a system: He would always write a note-for-note chart for you. If there was no chord symbol over a bar, you had to play it as written; if there was a chord symbol, you could either play the part or do something else you felt like doing. Looking back, I think the tracks where the real me came out are “Touch Me in the Morning” [by Diana Ross], 'Then came You” (by Dionne Warwick & the Spinners), 'Mama Can't Buy You Love' [by Elton John], “Midnight Train to Georgia' [by Gladys Knight & the Pips], and [guitarist] Dennis Coffey's 'Scorpio,' which had a 9O-second bass solo that's all me."

NASHVILLE CAT

By the late '70s, Bob's workload reached critical mass. "I was recording with so many different artists in so many different styles, I didn't know which end was up. I remember cutting three complete albums in three weeks at one point. The first was with the Spinners out in L.A.; then came an Alice Cooper record in Toronto; then I did Sinatra in New York. I didn't just have to play differently on each session; I had to dress differently."

Maybe it was for the best when things began to slow down in the early '80s--but "Chameleon Bob" was soon adjusting to a new work situation. Moving away from album projects, he cut jingles and filled up the rest of his schedule with a foray into jazz, touring and recording with flutist Herbie Mann and saxophonist Stanley Turrentine. It was no big deal. Babbitt had weathered slow periods before, and he knew the pendulum would soon swing back his way.

But it didn't. As the mid-' 80s approached, the golden era of the studio bassist was coming to an unceremonious end. Adjusting to the new realities of the session scene, some hitmakers landed lucrative touring gigs, while others faded away into club dates and teaching. Babbitt, like Willie Weeks, David Hungate, and other studio veterans, opted to head for what has become the last safe haven of real bass recording: Nashville.

"I knew a little bit about the town, because I had worked there briefly in 1976 on a Tracy Nelson session and again in the early '80s on an Ahmet Ertegun project," says Bob. "I'm not really a strict country player, but it was the most logical move for me because a lot of R&B influences were creeping into the traditional scene. There's also a busy gospel market in Nashville, and that's right up my alley. Even so, my first few years were kind of dry. There was a lot of demo work, and I did a few sessions with Louise Mandrell, Carlene Carter, and some other country artists. But I learned Nashville isn’t an easy town to break into. They don't care about what you did before. Most of the bigger sessions I was getting were out of town, like when Robert Palmer flew me to Italy to record Don't Explain [EMI].

"I've also made it hard on myself. You have to be in town to get the calls, and I've spent the last few years touring the world with Joan Baez and Brenda Lee. When I'm off the road, I'm usually playing with a local R&B band called Lost In Detroit. Dennis Locorriere, who was the lead singer for Dr. Hook, works with us, and we just tear it up in the clubs."

As for his uncanny ability to shift from one recording hot spot to the next while absorbing the necessary stylistic and technological changes, Bob has a simple answer: "I always seem to play with younger guys, and that keeps me current. It wasn't easy to learn to slap after 20 years of trying to perfect another Style, but the younger guys helped me to adapt. And Dave Hungate gave me a 5-string I’m still trying to get used to."

Unfortunately, no one has been able to help Bob deal with the same kind of typecasting Jamerson had to endure. "To this day, no matter what I do, no matter how many hits I've had away from Detroit, all anybody ever asks me is about Motown," he laments. "Even though the most important hits I did were at Motown, they never gave out gold records. I have more than 25 of them, and none are from Motown. What do people think I was doing for the last 25 years?”

BACK TO PHILLY

It’s the summer of '93, and Bob has returned to the scene of some of his earlier triumphs: Philadelphia's famed Sigma Sound Studios. The home of the "Philly Sound." But this time around, he isn't working with the Spinners, or the O'Jays, or Teddy Pendergrass; it's a greatest-hits session for '60s teen idol Bobby Rydell.

After plugging his '58 Precision into an ancient-looking Ampeg B-15, Bob warms up while being interrogated about his wrestling career by Philly's first-call baritone saxophonist, Bill Zaccagni. As Babbitt diplomatically sidesteps a question about how they rig the matches, it becomes apparent to the engineer and producer that this is no ordinary bassist. The sound is there instantly: big, fat, and round. Babbitt is ready for the downbeat.

He looks down at the bass chart for "Wild One" and sees every note written out, along with instructions to just read what's on the paper. As old as the song is, the job description is even older. But at this point in his life, Babbitt has made peace with it. "Hey," he laughs, "they're still calling me, so I figure I must have been doing something right for the past 30 years."

Back to top

Copyright Bob Babbitt. All rights reserved.